How to trace LGBT ancestors

8-9 minute read

By Mary Mckee | November 3, 2022

Mary McKee reveals the best ways to discover lesbian, gay, bisexual or transgender relatives in your family's past.

If you are hitting brick walls when trying to discover an elusive great uncle or great-great-aunt, did you ever consider the possibility that they were lesbian, gay, bisexual or transgender? Here are some suggestions and tips that can help to uncover the fascinating life stories of these ancestors.

Start your search

Discover relatives in billions of online records.

Our family trees are filled with people of all types, who lived extraordinary and sometimes ordinary lives. It is our task to discover as much as we can about our ancestors and record their stories. To do that, we cannot make assumptions or add our 21st-century ideas to their lives. In the last half-century, the Western world has become a more enlightened place for those who are lesbian, gay, bisexual or transgender (LGBT) – we still have further to go. Our ancestors were not met with the same level of open-mindedness or acceptance, leading them to live hidden lives. This makes discovering their stories and their truth a little more difficult – but not impossible.

Look for personal accounts

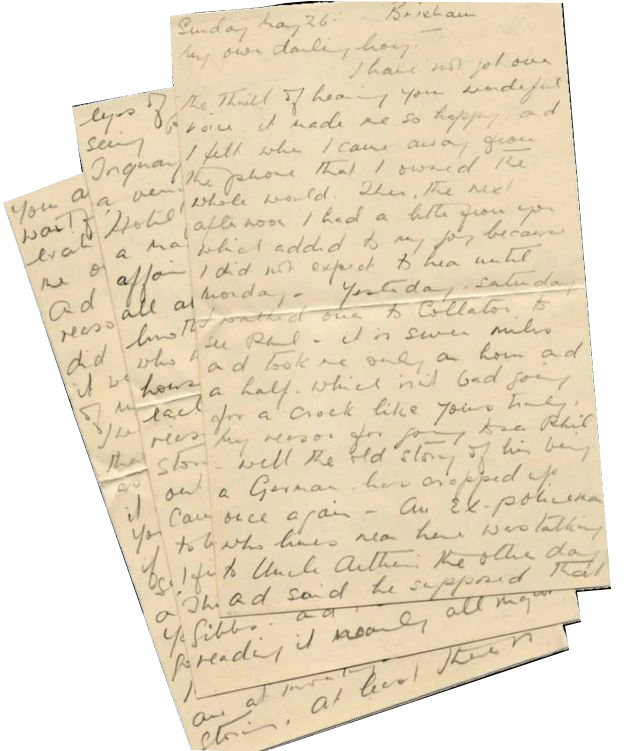

We are all jealous of that family historian who tells us about the trunks full of letters they inherited from their ancestors. Personal letters and diaries are the ultimate sources for understanding your ancestor’s thoughts, desires, and ambitions. Obviously, if you find passionate letters between your ancestor and a person of the same sex, there was relationship there. However, do not always expect to come to a clear conclusion about your ancestor’s sexuality. Women of the 19th century were known to have passionate friendships and write, what we would deem today as love letters. Those letters neither confirm nor deny a same-sex relationship, but they do confirm a passion and a love between the two people.

You never know where you will find these letters or personal effects. In 2008, a curator from a local museum in Oswestry, Shropshire, England found a series of letters on e-Bay. After he bought all the letters, he realised they were love letters between two soldiers who were serving in the Second World War. One of the letters stated:

""do one thing for me in deadly seriousness. I want all my letters destroyed. Please darling, do this for me. 'Til then and forever I worship you.""

Luckily for us, the letters were not destroyed, but the men were conscious of how dangerous this evidence could be if it fell into the wrong hands. At the time, homosexuality was criminalised in Britain and disclosing their relationship would have resulted in a court-martial.

One of the most poignant lines in the letters is:

""Wouldn't it be wonderful if all our letters could be published in the future in a more enlightened time. Then all the world could see how in love we are.""

Check old newspapers and court records

If you want to imagine the life your ancestor led, it is essential to understand the laws and customs that governed their life. For example, in 1882 it would have been unlikely that your British great-great-aunt would be in the local public house since it was legal to refuse to serve women in a bar there until 1982. It would be just as unlikely that your great-great uncle enjoyed a leisurely weekend off work since weekends off weren’t common until the 1930s.

The same logic applies to your LGBT ancestors. Gay men were criminalised in Britain until 1967. Lesbians did not face the same type of criminalisation, but were discriminated against in other ways. In cases of divorce, for example, fathers would often receive full custody of their children since many judges viewed lesbianism as a disorder. Support for transgender people was little to none and for centuries they were forced to find their own underground support networks or live a life in silence.

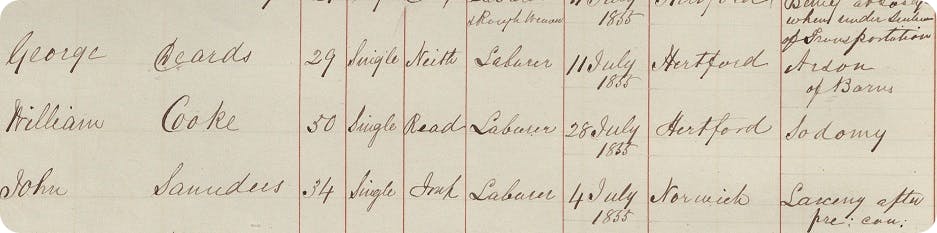

Since homosexual acts between men were criminalised, it does mean that there is a chance that you might find your ancestor’s name turn up in the courts or in the newspapers. For example, William Cooke’s unfortunate case can be found in the England & Wales Crime, Court and Punishment records. Cooke was sentenced to life in prison in 1855 at Hertford for the crime of sodomy.

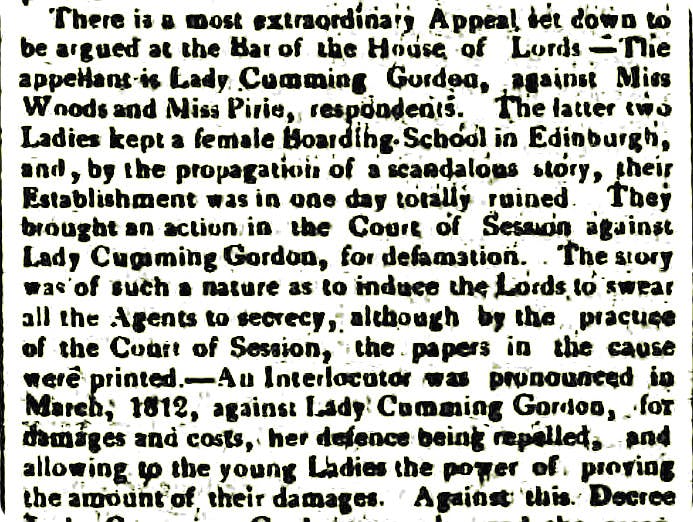

In other cases, you may find your ancestor in historical newspapers for appearing in court, not specifically for sodomy or gross indecency, but instead for libel or defamation charges. Such was the case of Marianne Woods and Jane Pirie, two Scottish teachers who ran a boarding school in Edinburgh, until a pupil accused them of 'unnatural behaviours'. The child's grandmother, Dame Helen Cumming Gordon, was influential and spread the rumour to encourage others to withdraw their children from the school. After the school closed, the two women went to court against Dame Gordon on charges of defamation. The newspapers from the time give us glimpses into the case but provide little details. The Lancaster Gazette wrote:

"“The story was of such a nature as to induce the Lords to swear all the agents to secrecy.”"

Lancaster Gazette, 2 March 1816

Fortunately, some of the court transcripts, which were ordered to be destroyed, have survived, and provide us with the details of the case. Of course, Woods and Pirie were arguing that the child made up the accusations, but the whole case does leave the relationship open to interpretation.

What do their wills reveal?

The wills created by LGBT people can reveal a good deal about their relationships and chosen families. For many of our LGBT ancestors, to live an open life, they often left home – or were forced to leave – and needed to discover a new network of allies, friends and a new chosen family. This circle of support is often exposed in their wills by who they chose to leave their worldly possessions to.

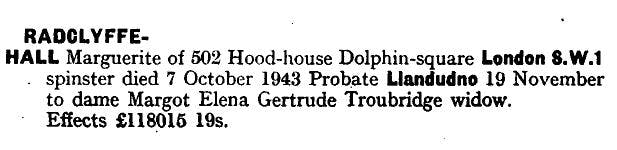

The author of the 1928 lesbian novel The Well of Loneliness, Radclyffe Hall’s entry in the probate index shows that her effects were left to Margot Elena Gertrude Troubridge, known to many by her nickname Una. The entry reveals that the two did have a relationship beyond companionship.

Source: Gov.uk probate index

In her life, Radclyffe was often referred to as John in letters and cards from her friends. This is something we do see that in other same sex relationships, but in some cases individuals lived by their masculine name.

Relationship to the Head of the Household

Census records are an amazing source for tracking long-term relationships, but the residents in a household weren’t open about their relationship status. But it is fascinating to look at how they do represent themselves under the watchful eye of the enumerator. Individuals had to deny their true relationship to each other, but some found a way to skirt around the obvious.

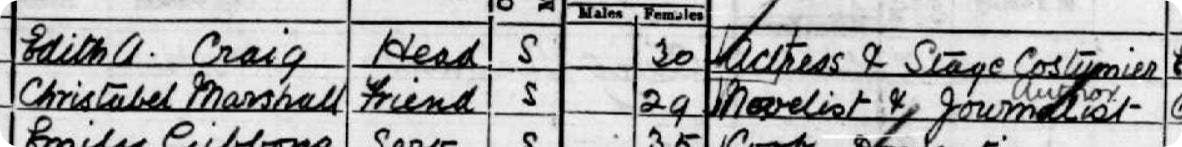

Edith Craig and Christopher St John lived together from 1899 and we can see them in the records together from 1901 until 1939. In 1901, the pair are living together with two servants. Christopher is register with their birth name, Christabel Marshall. It is remarkable that they are listed as ‘friend’ by the official enumerator. Not as a visitor or lodger, but as a friend.

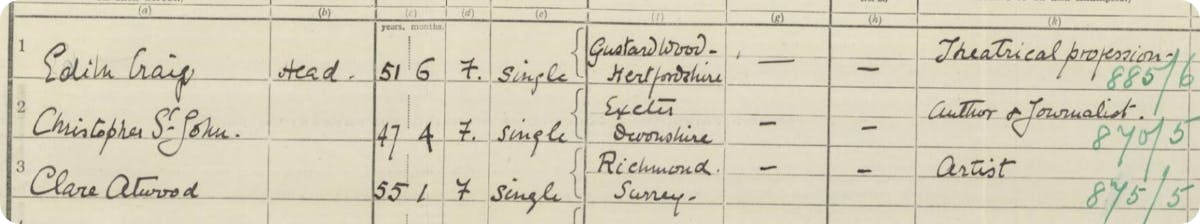

We cannot find the pair together in 1911; however, Christopher was heavily involved in the suffragette movement and may have been participating in the suffragette boycott of the census. We do find Edith and Christopher together in 1921. Christopher is living by their male name and has taken on the surname St John. Between 1901 and 1921, Christopher had converted to Catholicism and assumed the name St John in honour of St John the Baptist. In 1921, we also find the two in their home with the third member of ‘throuple’, Clare Atwood. In this census, Clare and Christopher completely omitted their relationship to the head of the household. Through their omission they refused to define their relationship for the bureaucrats.

We can continue to follow the three into 1939, where they are all living at Smallhythe Place. Their home became a centre for creative expression with its own theatre and welcoming spirit.

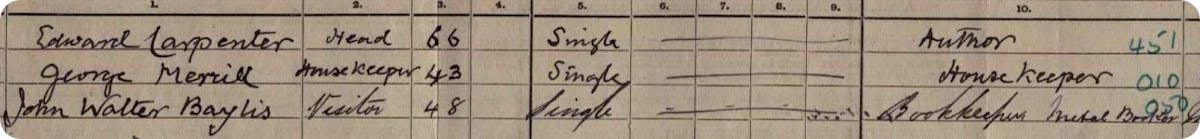

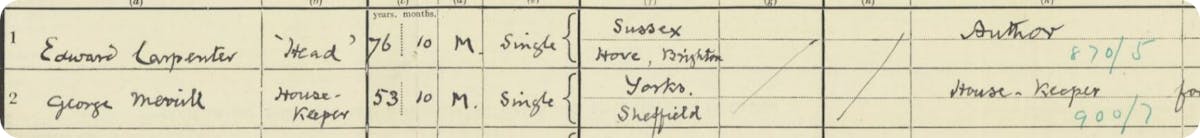

We can also follow the relationship of another well known couple in the census records, Edward Carpenter and George Merrill.

In both, the 1911 and the 1921 Census we find the couple together, but George has recorded himself as the housekeeper in both census. George was a poet and philosopher, but he was, officially, Edward’s housekeeper.

The pair’s relationship is said to have been the influence for both E M Forster’s Maurice and D H Laurence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover.

Delve into local history

Even though your LGBT ancestors were not accepted by wider society, they may still have experienced lives full of love and have been embraced by their social circles. There is a long history of private clubs, societies and public houses that offered a safe haven for LGBT people. For that reason, it’s important to understand the local history of the area where your ancestor lived. Was it known to be a progressive area? Is there evidence of activism or known clubs or societies in the area?

Get out there and explore the area where your ancestor is from. Look up local history societies as well as LGBT groups. Many groups will have individuals interested in history who might be actively documenting the LGBT history of the local area. Explore sources outside of the traditional genealogical records.

Watch out for 'missing records'

If your ancestor's records appear to be missing, that can tell you almost as much as finding their records. Throughout history, many families have tried to hide any evidence that their relative was lesbian or gay through a process of denial. This often leads to the destruction of family records and personal effects. If your family were known to keep family photos, documents and heirlooms, but nothing exists for one person, then it’s time to ask questions.

6 quick tips for tracing LGBT ancestors

LGBT people are (and were) everywhere. You might not find that definitive record or letter where they define who they are. We all can’t have an Anne Lister in our family tree, writing thousands of pages of diaries and openly declaring;

"“I love and only love the fairer sex and thus beloved by them in turn, my heart revolts from any love but theirs.”"

However, there are a few general tips you can follow for continuing your own LGBT family research.

- Never assume, generalise or stereotype.

- Use every resource around you and don’t just stick to traditional records.

- Explore more than just the individual – where did they live? What was happening in the world at the time?

- Sometimes official records can subtly divulge clues. For example, if your ancestor is shown on a census with a boarder over multiple years, it's possible they disguised a same-sex relationship as a landlord-tenant arrangement.

- It is possible that your LGBT ancestor assumed a new name or used a nickname among their friends. In lesbian circles of the '20s and '30s, it was common for women to refer to themselves as Jack or Tommy.

- Add same-sex relationships to your online family tree. We're constantly striving to make Findmypast a more inclusive experience for all of our members. For instance, when adding parents to your Findmypast family tree, assigning their gender is no longer mandatory.

About the author

Mary McKee has been working at Findmypast since 2014 as a Data Content Specialist. Mary grew up in Philadelphia but now lives in the country of her ancestors in Northern Ireland. She holds a Masters in Irish History from Queens University, where she developed a passion for LGBT history. When she is not working on her family tree or researching, Mary enjoys walks with her dog, Netflix binges, and spending time with family and friends.

Related articles recommended for you

Who Do You Think You Are? Series 21: here's what you missed

Discoveries

Finding Eli: A granddaughter’s story

Discoveries

We found war veterans and healthcare workers within Keir Starmer's family tree

Discoveries