Your new go-to guide for researching your Catholic ancestors

3-4 minute read

By The Findmypast Team | February 8, 2017

If you're tracing Roman Catholic ancestors, then here's a definitive rundown of where to start.

Our Catholic Heritage Archive is a ground breaking project that will eventually see as many as 100 million Catholic records published online for the first time ever. We've put together this comprehensive guide to understanding your search results.

Sacramental registers are the Roman Catholic Church's equivalent of the parish or parochial registers found in, for example, the Anglican Church, and what tend to be called metrical books in Russia and other parts of Eastern Europe.

While Anglican parish registers tend to comprise baptisms, marriages and banns, or burials, Catholic sacramental registers give a different, sometimes narrower but sometimes wider array of event types.

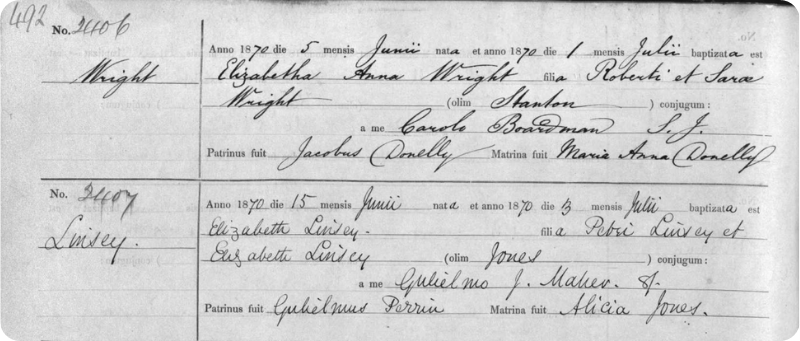

Baptisms are core to these. As well as details of the baptism date (sometimes birth date too) and parentage, Catholic baptism registers usually record the sponsors, or godparents, of the child. These may or may not be close kin of the baptised person, but are always worth considering during research. Another feature of Catholic compared to Anglican baptism registers is the much higher proportion of adult baptisms, i.e. of converts to Catholicism.

A Catholic baptism record, dating back to 1870. View this record here.

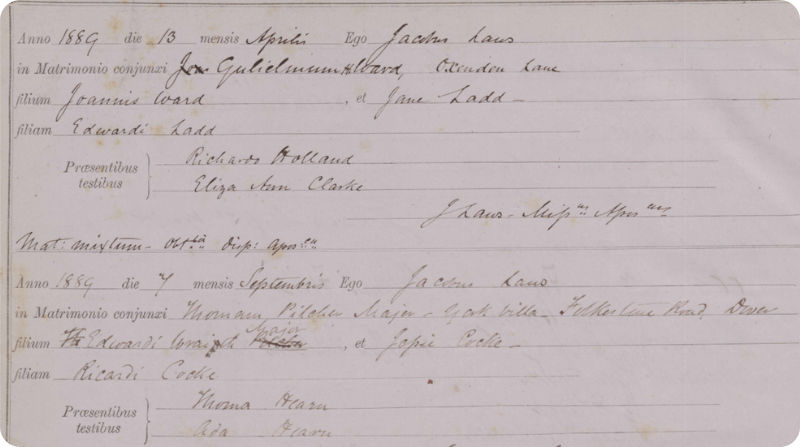

Banns – declarations of the intention to marry – are not a common feature of Catholic record-keeping, as the banns is not a sacrament, but a largely administrative and legal feature (permitting members of the congregation to object if they observe an impediment to the forthcoming marriage).

A Catholic marriage record, dating back to 1889. View this record here.

Of course, marriage is a sacrament, and Catholic marriage registers give all the matrimonial information you might expect and often more. Those in America, for instance, often give details of place of origin of the bride and groom, which is tremendously useful for immigrant ancestors (as the place of origin overseas is often vital in prosecuting a successful search when the home land is, for example, Ireland, Italy, Lithuania, Poland or Slovakia).

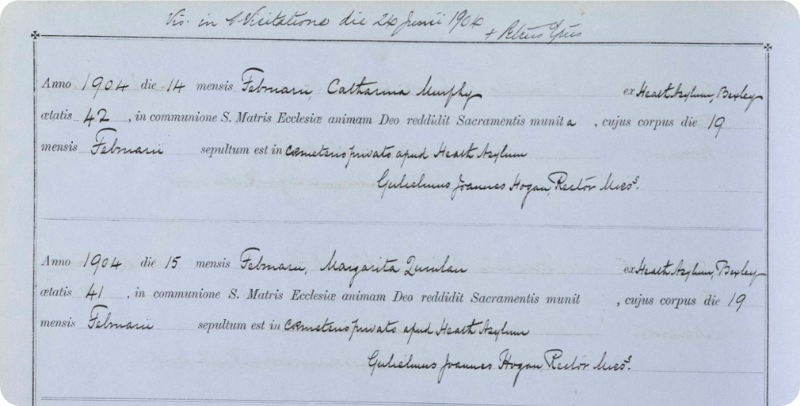

Burials do not feature as frequently in collections of registers from Catholic churches – it is rare to see an unbroken run of burials, or deaths, coinciding with the baptisms and marriages for the same congregation. Anointing of the sick (extreme unction) is a sacrament in the Catholic Church but not one which produces regular records.

A Catholic burial record, dating back to 1904. View this record here.

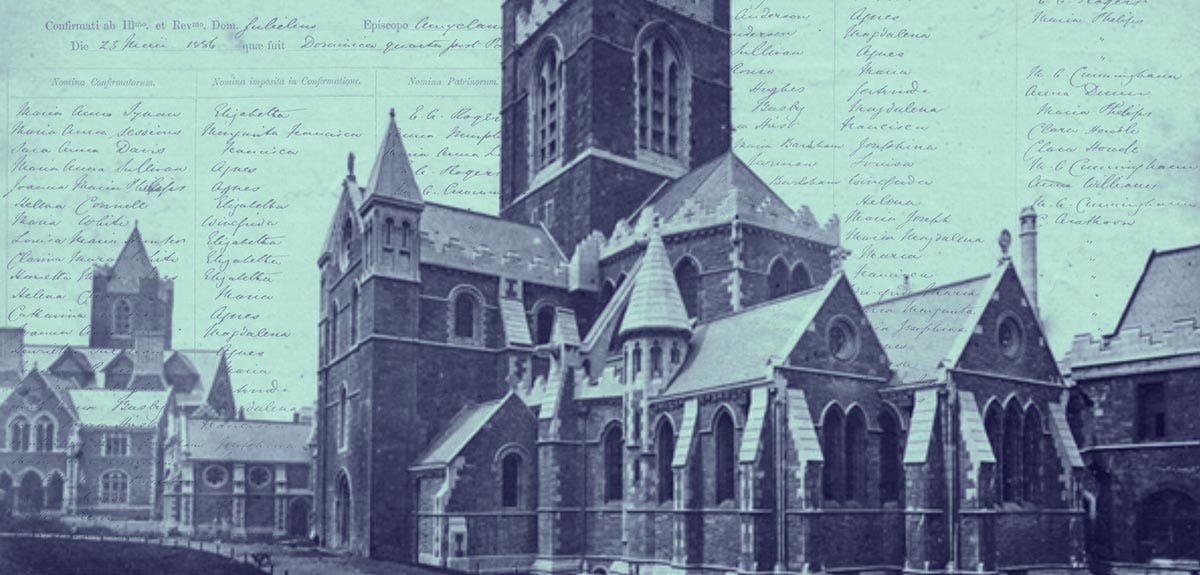

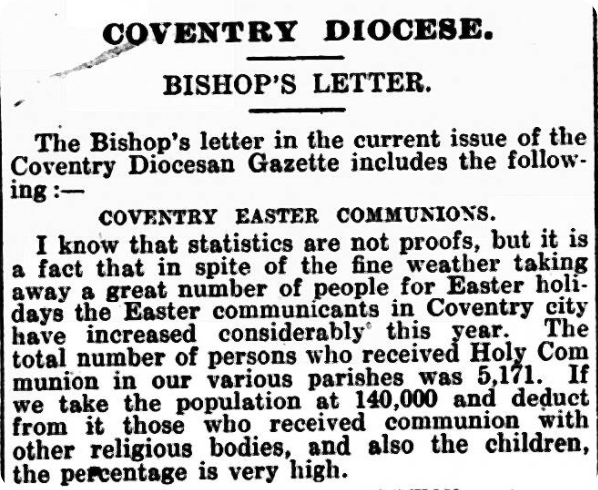

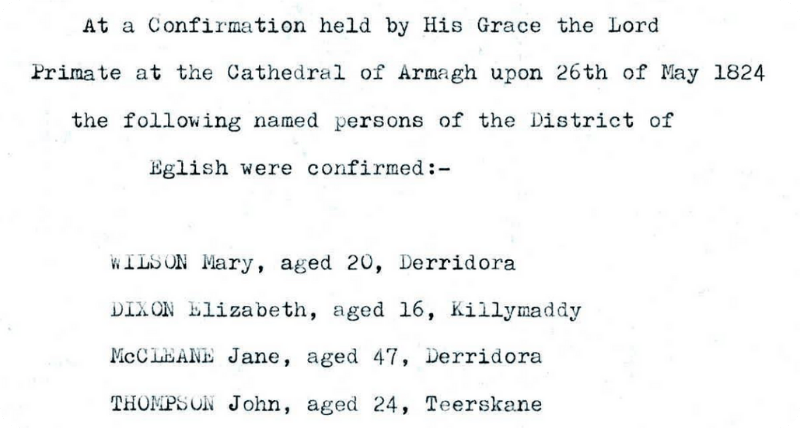

First Communion (at the age of reason) and Confirmation (at the age of discretion) are important Catholic sacraments initiating the subject into the Church. Lists of communicants, such as this collection from Scotland, are relatively common, as are lists of confirmations, such as this one from Ireland. They usually give the age of the subject, from which approximate birth year can be calculated. Note that sometimes confirmation occurs only at a bishop's visitation – if such visitations were infrequent, then confirmation might occur at a later age than one might expect. Separate lists of Easter communicants may also be seen.

An article noting high numbers of Easter communicants, 1921, Warwick and Warwickshire Advertiser.

For genealogical research, these are bonuses, perhaps, rather than core records. Think, for instance, of situations where a Catholic child is born and baptised in another country but has his or her first communion and confirmation into the faith in the immigrant land. Whether such records are available for a particular church depends, of course, upon whether they were produced by the priest and whether they were preserved and deposited in the archive.

A list of Irish confirmations dating back to 1824. View this record here.

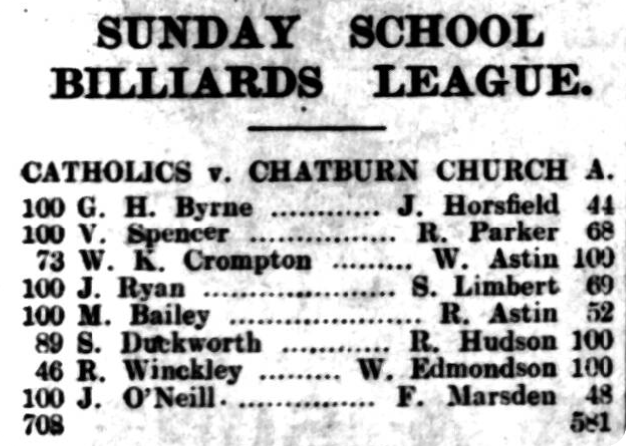

Other event types which sometimes occur in parish archives include anniversaries (memorials of the dead); censuses (of all Catholics in a diocese) convalidations (the Catholic blessing and recognition of a marriage which took place previously outside the Catholic Church); catechisms; conversions; mass intentions; confraternity lists; congregation lists (lists of souls); and Sunday School lists.

A Sunday School Billiards League report, from the Clitheroe Advertiser and Times, 1936.

Some of these may be culturally or geographically specific – they may feature in archival volumes from one archdiocese but not the next – and it is quite rare to find these in the collections being digitised for online publication. Generally, you should expect baptisms and marriages for a parish as a minimum and regard anything else is an unexpected - and useful - extra. Make sure to also check out our newspaper archive for extra morsels of information. Local newspapers would often report on fundraising events, sports fixtures, and more.

Lost in Latin?

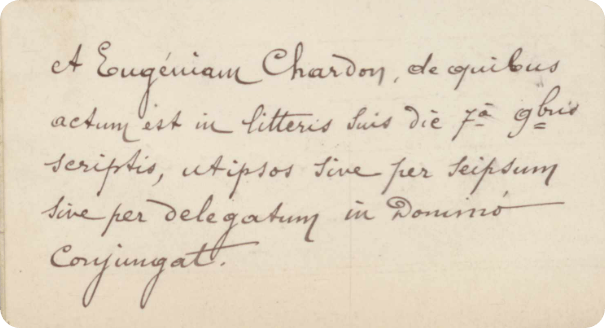

Latin was the everyday performative language of the Catholic Church and therefore record-keeping was traditionally in Latin. Towards the end of the 19th century, generally there was a gradual switch to the vernacular but it's not unusual to see mid- and late 20th century records still being composed in Latin. Some register formats are hybrid: for example, a printed register might have Latin column headers but the text written in by the priest will be in English or other language of the congregation.

The use of Latin is not usually too problematic, as the records for a particular time and place tend to follow a common format, meaning that the key elements can be extracted even when one isn't fluent with Latin. However, Latin can introduce some challenges for a family historian not entirely familiar with the dead language.

A note found in our Catholic marriage records, entirely in Latin. View this here.

Firstly, Latin is a language in which proper nouns such as forenames may decline to show grammatical case. For example, depending on sentence structure, a male forename may be written in the nominative case (e.g. Jacobus), the accusative case (e.g. Jacobum), or the genitive case (Jacobi). The equivalents for women are Maria (nominative), Mariam (accusative) and Mariae (genitive).

Secondly, as you can see from the examples above, the priest may use the Latin version of the vernacular Christian name. For example, an Irish or Scottish Catholic James might be known as Jim, Jimmy or Seamus to family and friends, but he will appear in the register as Jacobus. Of course, this can create problems of reverse translation – what if the child's name actually was Jacob, for example? Most forenames in English have multiple equivalents in European languages – e.g. John has its counterparts in Evan, Giovanni, Hans, Ivan, to name but a few. To a Latin-speaking priest, all of these might be rendered as Johannes in the register.

Once you've mastered your sources, and gotten the hang of Latin translations, you're on a roll. With our extensive Catholic record collections, spanning from England, Scotland, Ireland, America, and beyond, you have everything you need to trace your Catholic ancestors.

Related articles recommended for you

New records from Scotland to Staffordshire

What's New?

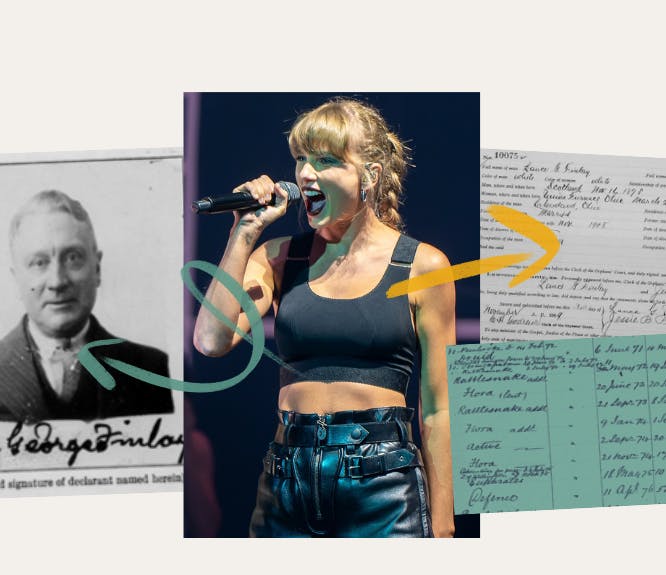

Taylor Swift’s family tree shines with love, heartbreak and the triumph of the human spirit

Discoveries

Celebrating Irish stories with almost a million new records

What's New?