A Bleak History: Dublin workhouse records allow you to find the voices of the voiceless

2-3 minute read

By Niall Cullen | May 15, 2015

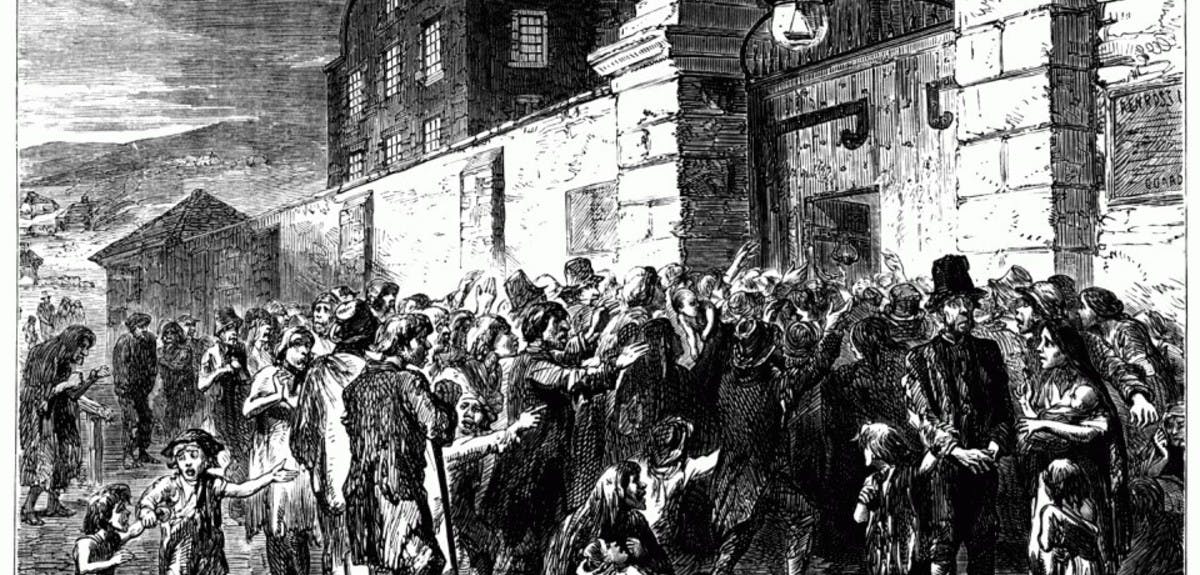

Workhouse. It's a word that conjures up horror in Irish stories, a place of no escape, of utter destitution. The Irish are a proud people and the thought that your ancestors, your people, had been forced to accept the deprivation and tyranny of the workhouse was too much. During Ireland's War of Independence, squads of rebels would burst into the old workhouse buildings to torch the records, so that any evidence of their families past shame were destroyed. Long after they were closed down the memory of the workhouse lingered on as a bogeyman to keep the kids quiet. They were grim places, there's no doubt about that.

Explore new and exclusive Dublin workhouse registers

The oldest and the youngest found their way into Dublin's workhouses because there was nowhere else to go. They came to those forbidding buildings because they had no one to look after them. Some of them were in need of medical attention, others just needed a roof over their heads, food in their stomachs. These were the people who the workhouses were built for. There were a lot of poor in 19th century Ireland and Dublin was where many of them came to. You can find their stories exclusively on Findmypast in the records of four Dublin workhouses. With over 1,500,000 admission and discharge records and 900,000 records from the meetings of the Boards of Guardians you will be able to uncover details of some of the poorest, most vulnerable people in the country over an 80 year period. These are the people who tend to leave no traces in recorded history, the forgotten members of society, the silent.

The Irish Poor Law had been brought in in 1838, four years after the new Poor Law for England and Wales. Under these new laws, the country was divided into unions, overseen by a Board of Guardians made up of elected ratepayers. Each union maintained the district's workhouses, managing the staffing, building and matters of discipline and money. They organised foster mothers and wet nurses for abandoned children, saw that the workhouses had sufficient supplies and basically made sure the system ran smoothly. The system had barely been up and running for five years when the Great Famine started.

For the next 80 years the workhouse loomed large in the Irish psyche, casting a shadow which still causes shivers today. There had been warnings in the early days that the system would not work in Ireland. Church of Ireland Archbishop of Dublin Richard Whately had warned that the causes of Irish poverty were different from those in England and Wales back in the 1830s. He had warned that Irish poverty was so bad because there was so little work. Poverty was not avoidable and hard to escape. The workhouse emphasis on acting as a deterrent could not work in these conditions. Once people went in as indoor paupers it was hard to leave again.

Life in the workhouse was intentionally hard for the inmates. Families were separated and food was only marginally better than the starvation rations they had eaten on the outside. Days rocked between gruelling work and endless boredom where anger and spite could become sport. Even in these conditions love sometimes flourished. The Board of Guardian minute books sometimes record the marriage banns of couples who had managed to come together despite rigid separation. Couples like William Field and Maria Leech or James Whelan and Mary Manning found love in 1850 in the South Dublin union workhouse.

These are just some of the stories that you can find in the Dublin Workhouse Admission and Discharge books and the Dublin Board of Guardians minute books now available to search on Findmypast. Given how precarious life could be in the 19th century, who will you find in there?

This blog was contributed by Abigail Rieley and Brian Donovan. Abigail is a content curator for Findmypast and specialises in social history and crime. Brian is the Irish Records Expert at Findmypast. He has been digitising and indexing Irish historic records since 1998. He formerly lectured in history at Trinity College Dublin and was a founding member of the Irish genealogy company Eneclann. He has played a central role in creating the Irish record collection at Findmypast and continues to oversee its development.

Related articles recommended for you

Irish family history and minority religions in Ireland

History Hub

From Ulster to the US: Irish migration patterns and their impact on Irish genealogy

History Hub

The shocking true story behind Wicked Little Letters

History Hub